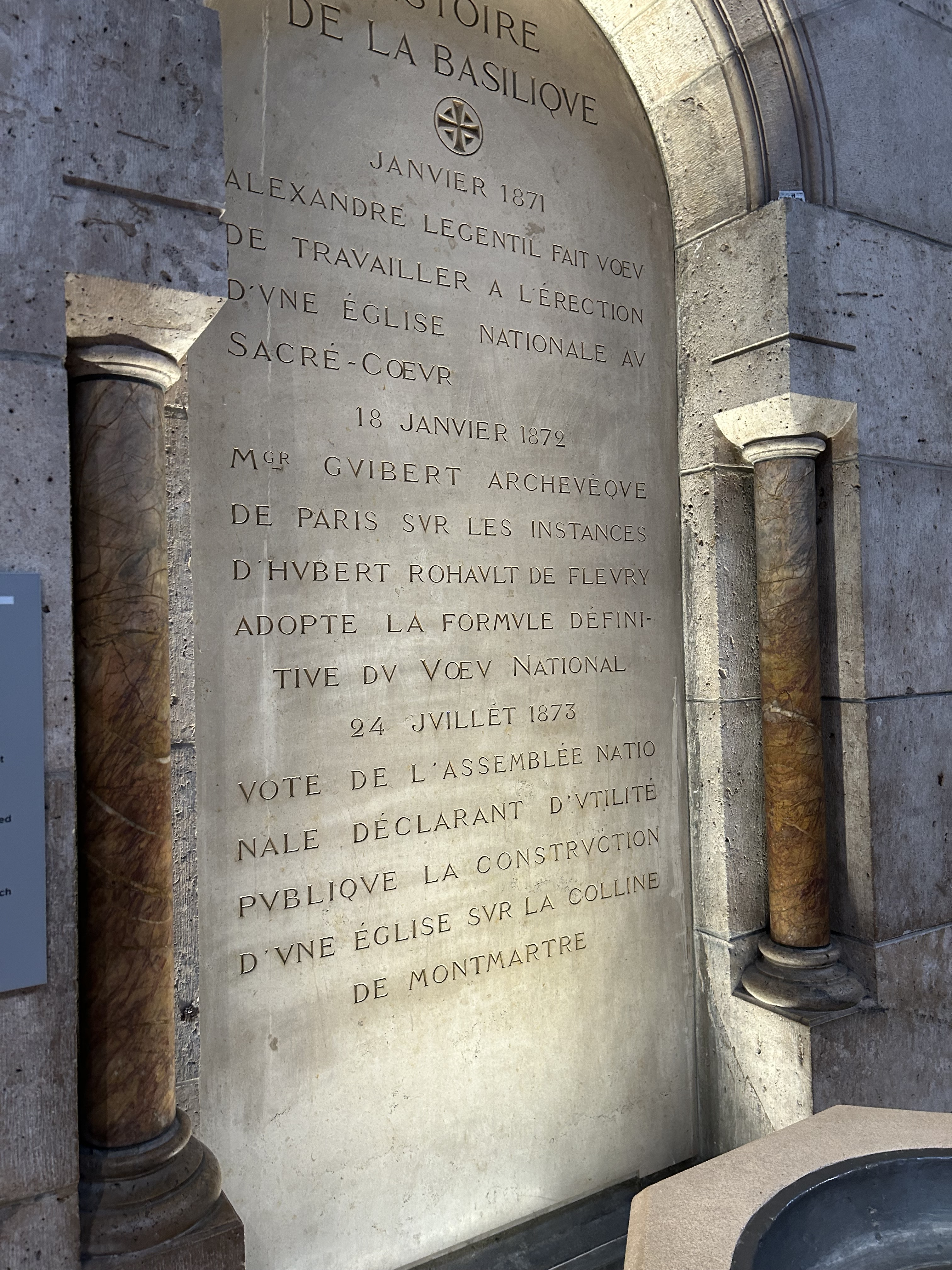

While doing the walking tour of Montmartre, I noticed a very strong geographical irony that I initially could not understand because it depicted groups who violently clashed commemorating their heroes simultaneously within very small space. First of all, I was confused as to why a statue of a headless religious figure who was chased, tortured, and decapitated by local rebels was less than a mile a way from Sacré Cœur, one of the most beautiful churches I have ever seen. The obvious clash between the church, and the intellectuals and artists made this set-up very confusing. During the tour, we learned that the church was next to one of the first Parisian public schools opened up during the 1840s which was founded by a woman who was a fierce rebel and whom was ultimately exiled. Similar to the irony in the headless statue being close to the church, this woman’s school is oddly close to the church as well. We also learned that the church was built after the revolution by conservative individuals looking to essentially cleanse the city of the “sins” committed by and perpetuated by the rebels.

Aside from the irony, this church was the biggest and grandest church I have ever seen. In the church itself, each room had a sub-room or corner dedicated to different saints. The ceiling was painted beautifully, and it was simply one of the most spectacular buildings I have ever stepped foot in.

After doing some reflection, I realized that this seeming irony is irony on its face but makes sense in the broader Parisian revolutionary context. I went into the walking tour with an American historical lens on, meaning that I expected to see distinct places dedicated to specific groups and not others. I expected the religious buildings to be far from historic rebel landmarks, especially infrastructure like a public school. What I have gathered from this tour is that Paris or at least Montmartre is a place that attempts to tell both sides of the story, which is often something that is lacking in the United States. While museums often tell a fuller story than a singular statue, Montmartre’s diversity of monuments allowed me to understand clashing perspectives during the 1840s revolution. So far, Paris as a whole seems like a city that maintains its history from both sides of the revolution. Overall, visiting Montmartre challenged my assumption surrounding the spacing of statues, landmarks, and churches in relation to the 1840s revolutionary events.