In the 1820s, John Martin created a series of paintings depicting catastrophic events, featuring vast, dreamlike spaces and dramatic lighting effects reminiscent of nightmares. These paintings were heavily influenced by John Milton’s “Paradise Lost” and the biblical Apocalypse.

One of Martin’s works from this series, “Pandemonium,” painted in 1841, draws inspiration from a passage in the first book of Milton’s “Paradise Lost.” In this passage, “Pandemonium,” the palace of Satan, emerges suddenly from the depths. In Martin’s painting, we see a sprawling complex of buildings extending along the waterfront, depicted with his characteristic diagonal perspective. This imagery echoes the fantastical reconstructions of ancient cities.

In the foreground, Martin portrays Satan, depicted as a figure reminiscent of an ancient Greek hero, standing on a rocky outcrop. He bears a shield and a feathered helmet, akin to Achilles outside Troy. However, instead of leading besiegers, he commands an army of demons and damned souls within their Cyclopean city

As I strolled through the majestic halls of the Louvre, my eyes were drawn to this mesmerizing painting that was vibrant with energy. This masterpiece offers a chilling depiction of chaos and upheaval. Standing before it, I couldn’t help but feel transported to a tumultuous moment in history, where the echoes of revolution reverberated through the corridors of power.

Martin’s painting, with its dark and foreboding atmosphere, captures the essence of pandemonium—the infernal chaos that ensues when societal structures collapse and order gives way to disorder. The scene is dominated by swirling clouds of smoke and fire, hinting at the destruction wrought by revolutionary fervor. Amidst the chaos, figures writhe in agony, their contorted forms a stark reminder of the human cost of upheaval.

As I gazed at the painting, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to the tumultuous period of the French Revolution. The revolution, with its lofty ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity, unleashed forces of change that reverberated across the continent. Yet, like the chaos depicted in Martin’s painting, the revolution also gave rise to violence, bloodshed, and uncertainty. “Pandemonium” serves as a haunting reminder of the darker aspects of revolution, challenging romanticized notions of upheaval and societal transformation.

Moreover, the setting of the Louvre itself adds another layer of significance to my experience. As one of the world’s premier art institutions, the Louvre stands as a testament to human creativity and ingenuity. Yet, nestled within its hallowed halls are reminders of our darker past, such as Martin’s “Pandemonium,” which force us to confront uncomfortable truths about humanity.

In reflecting on Martin’s painting within the context of the French Revolution, I am reminded of the complex interplay between art, history, and memory. “Pandemonium” invites viewers to grapple with the contradictions inherent in revolutionary movements—to acknowledge the aspirations for a better world while confronting the realities of violence and upheaval. In doing so, it serves as a powerful testament to the enduring relevance of history and the importance of grappling with its complexities.

As I walked away from Martin’s haunting piece, I carried with me a newfound appreciation for the role of art in shaping our understanding of the past. “Pandemonium” had offered me a glimpse into the tumultuous world of revolution, reminding me of the enduring power of human creativity to capture the essence of historical moments and provoke reflection on their significance.

Continuing my journey, I ventured into the medieval part of the Louvre, where the remnants of the ancient castle still stood. Walking through its stone corridors and climbing its winding staircases, I was transported back in time. I imagined the bustling life of a medieval fortress—the clatter of armor, the shouts of soldiers, the many construction workers who built it, etc.

Despite the chaos depicted in Martin’s painting, the medieval section of the Louvre exuded a sense of calm and stability. Its imposing walls and sturdy ramparts stood as a testament to the resilience of the human spirit. It was a humbling experience to be surrounded by such tangible reminders of the past, to feel the weight of history beneath my feet.

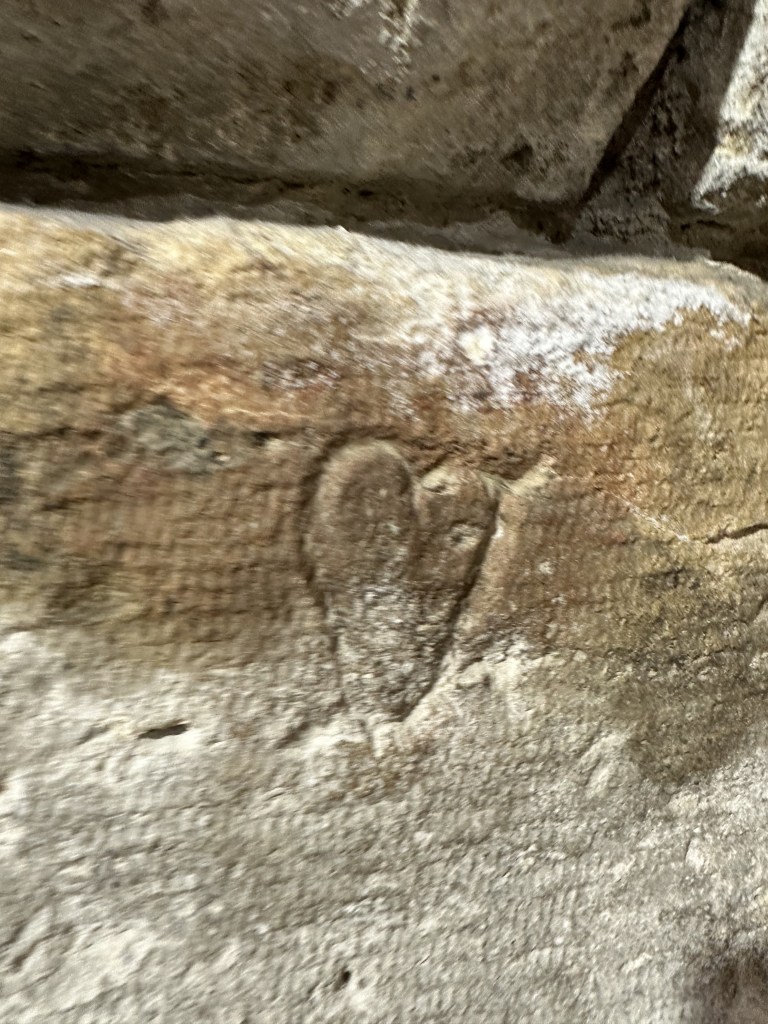

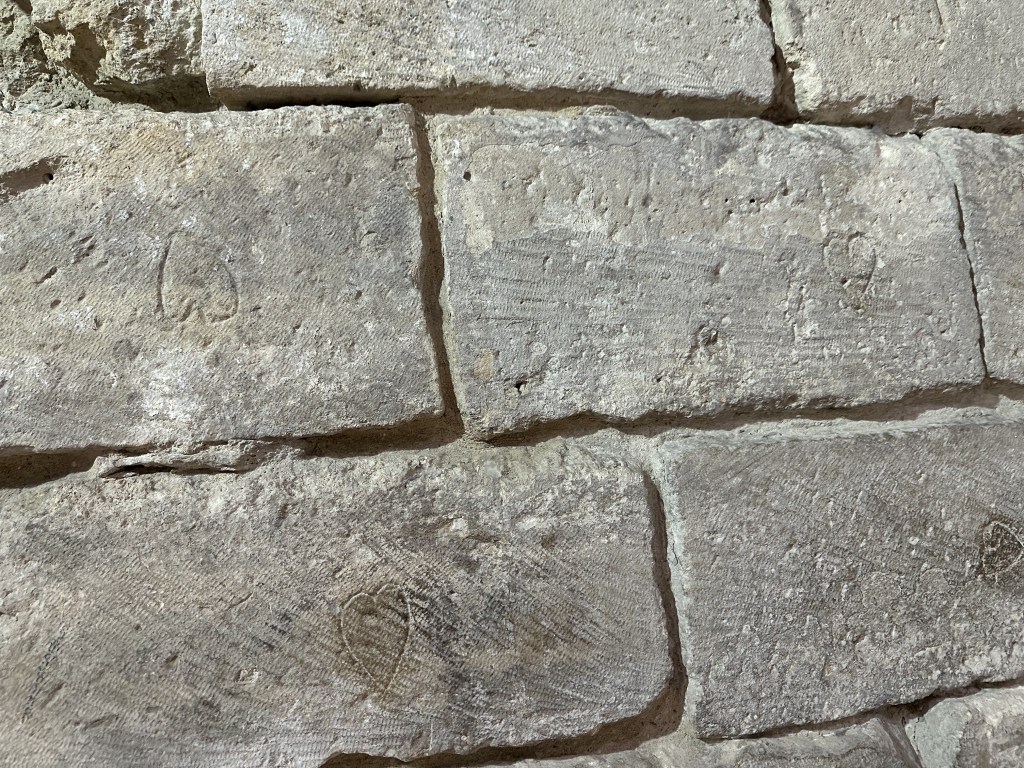

I especially enjoyed the markings of hearts, stars, and other shapes that were to keep track of the various construction teams at work during the creation of the castle, still here for us to see today.

As I emerged from the depths of the medieval Louvre, I couldn’t help but reflect on the contrast between chaos and calm, upheaval and stability. The juxtaposition of “Pandemonium” and the medieval fortress served as a powerful reminder of the complexities of human history. In the face of revolution and turmoil, the Louvre stood as a beacon of endurance, a symbol of the enduring power of human ingenuity.

My journey through the Louvre was not just a walk through history; it was a glimpse into the myriad facets of the human experience. From chaos to calm, from upheaval to stability, the Louvre offered a window into the past unlike any other. It was a journey that left me with a deeper appreciation for the rich tapestry of history that surrounds us, reminding me that the past is not just something to be studied, but something to be experienced and cherished. Walking through places that great others from history also walked through is a much stronger and impactful experience than simply reading about history or looking at photos. I still find myself in awe whenever I see a painting, artifact, or sculpture of a building hundreds of years ago with different inhabitants and purposes, yet that I am able to walk through them in the present in a totally different world.