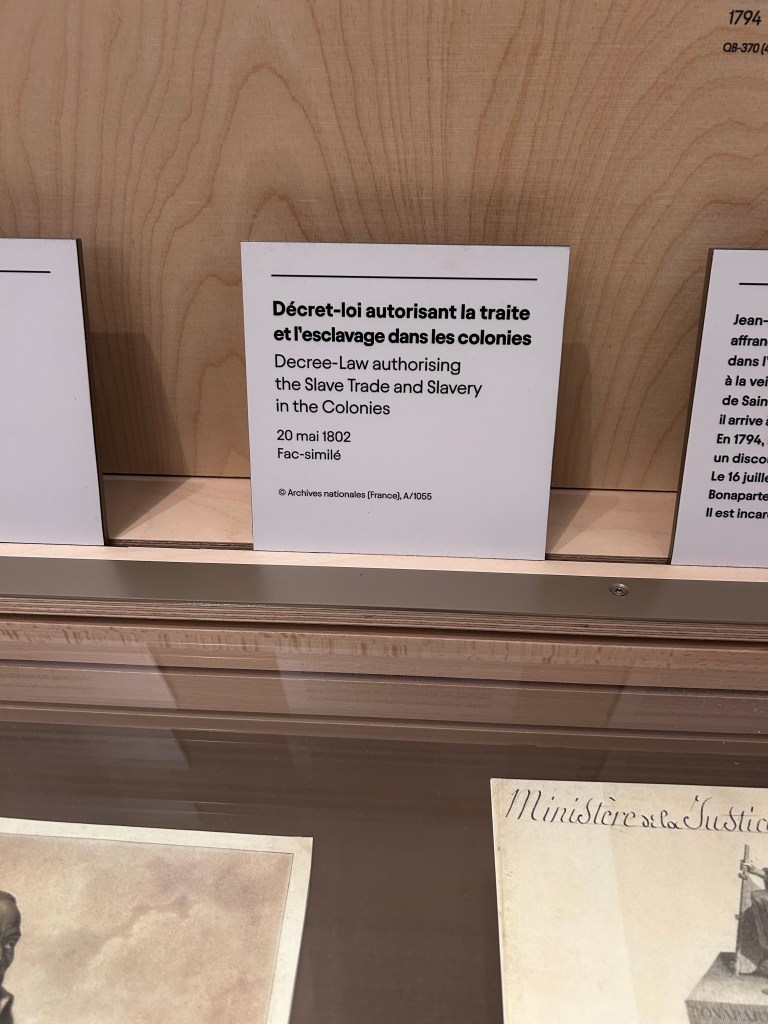

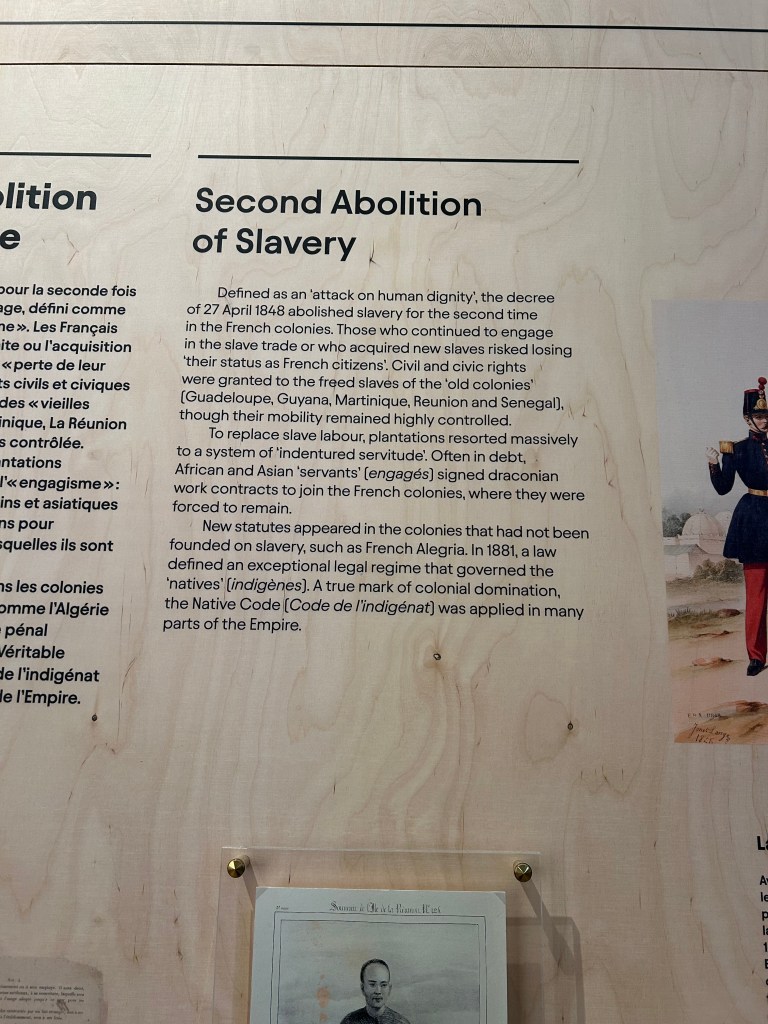

Touring the French immigration museum opened my eyes to a side of French history that I did not know existed. I had no idea that the French abolished slavery in 1794, made it legal again in 1802, then outlawed it again for good in 1848. I had no idea that the French held a Colonial Exposition attempting to justify its presence in the colonies.

I had no idea that men from the colonies came to serve on behalf of the French forces and received no rights after their service. Similarly, men from countries such as Poland were allowed to immigrate during the First World War for labor/service purposes. Some of these men were clearly children. To me, this demonstrates the dire need to live in France, even as a child laborer. The contributions of both those who served and worked on behalf of the French clearly contributed heavily to society, and yet, were not rewarded with respect nor (usually) rights.

When walking around Paris or Marseille I saw no memorialization of commemoration of immigrant workers who crucially helped the French during World War I and later through World War II. Although, this is not surprising considering that the Colonization Exposition was in 1931. The pure irony in having a dehumanizing exposition of people and their cultures after many people risked their lives for the French is disgusting and demonstrates this xenophobia that infected many powerful countries including the United States. The exposition itself was literally set up as if it were a zoo or carnival invoking a sense of cultural “superiority” amongst French people. Another irony is that fact that the French were attempting to justify colonization and the exploitation of individuals and resources after these same individuals risked their lives for the French.

This transition from exclusion, xenophobia, and racism was gradual but not a total transition, meaning that these modes of discrimination still exist, but they are sometimes combatted more often. For example, throughout the museum they preserved posters from a variety of protests. Some included immigration policy, police violence, prison treatment, expulsion, racism, and so much more. These posters were not surprising, considering many people living in powerfully democratic countries exercise their right to protest; however, it is interesting to examine the cultural shift from exposing other cultures in which the French exploited to protesting for more lenient immigration policies. Obviously, people change and generations most certainly change, but it is worth recognizing that this change stemmed from a lot of contradictory history.

When considering France’s timeline in going back and forth on the abolition of slavery and how it allowed immigrants into the country for labor and service without awarding them rights, the history is objectively contradictory. It was often noted that France was/is more welcoming to immigrants because of its history of exploitation and its involvement in deporting Jewish people to nazi Germany. It is difficult and impossible to conclude whether or not policy or changes in attitude are attributed to guilt or empathy, but regardless, this shift in the French perception of immigration is stark.

In terms of other protested issues like police brutality, the history of recognizing racism in tandem with police violence is also contradictory. In the museum, one of the protest posters that included police brutality was from 1999. In 2018, the French government removed the word “race” from its constitution. Although race and police violence were recognized as a linked issue in 1999, this perspective is attempted to be erased in 2018 by the French government. Similar to the way in which immigration attitudes shifted drastically, so did the understanding of the importance of race in acts of police violence. Overall, the immigration museum was fascinating because it mapped out cultural attitudes, policies, and legislation on a broader global timeline.